ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Could MCEDs work better in symptomatic patients?

Using speech to diagnose depression

Bird Flu Update: Ducks with H5N9 raise reassortment concern

An at-home test for bladder cancer that’s high-tech and simple

When it’s detected early, bladder cancer can be cured 90% of the time. But in 70% of cases, it eventually comes back. Currently, the most accurate way to see whether the cancer has returned is cystoscopy: Inserting a tiny camera through the urethra and looking at the inside of the bladder. Ouch.

A study in Nature Biomedical Engineering describes an option that would be much easier for patients. It’s a urine test that could be used either at point of care, or - even better - at home.

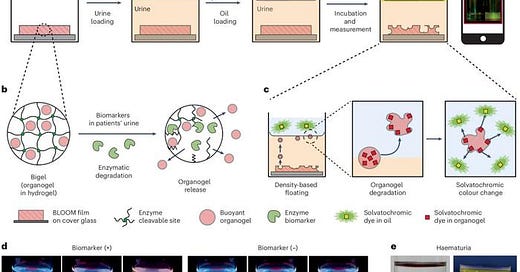

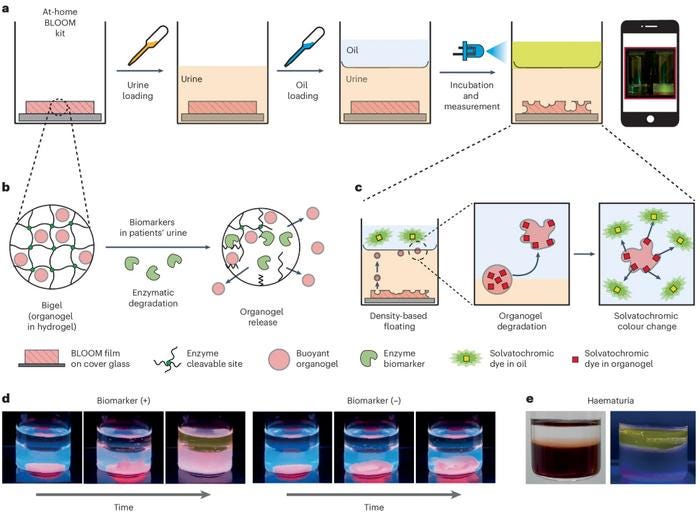

The test relies on the simplest of scientific facts: Oil floats on water. The test material is a gel that, like oil, is less dense than water. When the biomarker for bladder cancer comes in contact with that gel, the gel breaks up. Bits of it float into an oil layer at the top of the test vial, where they break down into a material that glows under ultraviolet (UV) light (see image here).

The trial was relatively small (80 samples from folks with various diseases, including bladder cancer, and 25 samples from healthy people). But at 89% sensitivity, it is a big improvement over the 20% sensitivity of most tests of its kind. (Cystoscopy, mentioned above, is a different thing.) It is also able to detect early-stage cancer, which currently available tests can’t do.

COMMENTARY: We love the apparent simplicity of the test. This exciting development fits in with our belief that health care is moving to point of care and home testing.

Using MCEDs in symptomatic patients may be the way to go

Most discussion of multi-cancer early detection (MCED) tests focuses on screening healthy individuals with no pre-existing risk factors. In that population, as we’ve mentioned before, the problem of false positives can be significant. A paper in Nature Communications looks at a different challenge. What happens when a person’s symptoms prompt their primary-care clinician to refer them to a cancer specialist? Turns out, 93% of the time, those patients don’t have cancer at all. In the UK, for example, this results in 1.9 million unnecessary specialist visits, taking time and attention away from patients who really need it.

Primary-care screening tests for cancer exist for only 30% of cases (involving cervical, breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer). The other 70% must be performed by an expert. The problem is compounded because suspect symptoms are often shared across many cancer types, so there is no guarantee that the correct specialist will get the referral.

This may end up being a place where MCEDs can help. The one presented in the paper uses a novel approach to raise its positive and negative predictive value in patients who have cancer symptoms. (Positive predictive value is the likelihood that a positive test result is right. Negative predictive value is the likelihood that a negative test result is right.) As is typical for this kind of test, it uses a proprietary (unpublished) algorithmic mix of chromosomal aberrations, individual mutations, methylation patterns, protein levels, and other criteria. The test also looks for epigenetic / methylation patterns that are typical of specific tissues, thereby helping to identify the cancer’s tissue of origin.

COMMENTARY: What is perhaps most valuable here is the possibility of a test that can offer help to patients with symptoms that could mean cancer but who don’t yet have a specific diagnosis - or to patients whose blood work indicates that they probably have cancer but doesn’t provide a clue as to where it’s coming from. Clearly MCEDs can at least help to triage these folks into high, average, and low risk groups before referral.

Can AI detect depression using a one-minute speech sample?

Depression is increasingly treatable once diagnosed, but in many cases diagnosis is delayed or never happens. Back in 2009 the US Preventive Services Task Force started recommending screening in primary-care visits, using a simple nine-step questionnaire (the PHQ-9, shown here). However, according to a 2018 study, that screening only happens in about 1.4% of primary-care visits. In addition, one of the symptoms of depression is to not seek medical care. When you have depression, it can be hard to do anything at all.

For that reason, a tool that minimizes the amount of effort a depressed person has to make to get a diagnosis would be helpful. The Annals of Family Medicine published a brief report assessing one such tool. It’s a machine-learning-based diagnostic that uses a short recording of a person’s speech as a sample. The paper found that the tool’s diagnosis of moderate to severe depression was correct 69% of the time. When it said a person did not have moderate to severe depression, it was right 75% of the time. (Important note: Three out of the five authors of the paper are employees of the company that makes and sells the tool.)

COMMENTARY: When something goes wrong with the brain, it almost always has behavioral consequences that could serve as early-warning “biomarkers.” Neurodegenerative disorders can affect movement patterns (e.g. gait in the case of Parkinson’s), and mental-health (aka affective) disorders can affect speech. It is estimated that roughly 30% of us will suffer a major depressive episode at least once during our lives, and that is almost certainly an underestimate.

One challenge in mental-health diagnosis is that there is no truly objective gold standard. This study compares AI-based voice diagnosis to PHQ-9 score, but a 2001 study that compared PHQ-9 to a (blinded) mental-health-provider evaluation found that the questionnaire underestimated 66% of major depressive disorders, while correctly ruling out 93% of those with no/mild depression - a low bar for a gold standard.

We are often skeptics of broad screening, but not in this case. Any major depressive disorder caught for active intervention is a success.

Bird Flu Update

Both H5N1 and H5N9 found at California duck farm

Both H5N1 and H5N9 influenza viruses have been found in ducks on a farm in California. The presence of H5N9 (another highly pathogenic avian influenza) “is bad news,” Dr. Angie Rasmussen, virologist at the University of Saskatchewan, said on Bluesky. It suggests that H5N1 is exchanging genetic material with other avian flu viruses, a process called reassortment. “Reassortment makes pandemics. The last three out of four flu pandemics (and likely 1918 too) were reassortant viruses,” Rasmussen said.

According to KFF Health News, two CDC reports on bird flu were slated to appear in the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report last week. One addresses the question of whether “veterinarians who treat cattle have been unknowingly infected by the bird flu virus.” The other looks at the question of whether people can pass the virus on to their pet cats. (Four more domestic cats were confirmed infected this week, two in South Dakota and one each in California and Oregon.)

COMMENTARY: We hope that the administration’s requirement that federal health agencies cannot publish any document “until it has been reviewed and approved by a presidential appointee” is lifted quickly so we can all learn more in a timely fashion.