They said you could use someone’s bacteriome to diagnose cancer. Other folks checked their results.

Volume 8, Issue 9 | August 9, 2023

In This Issue

AI-assisted prenatal ultrasound

ProMED is broke - and why you should care

The pandemic delayed cancer screening - and it matters

New and Noteworthy

A new entry on the already long list of AI-assisted imaging: prenatal ultrasound

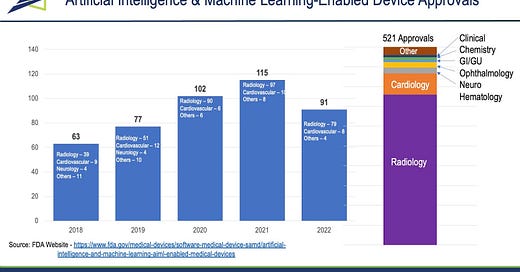

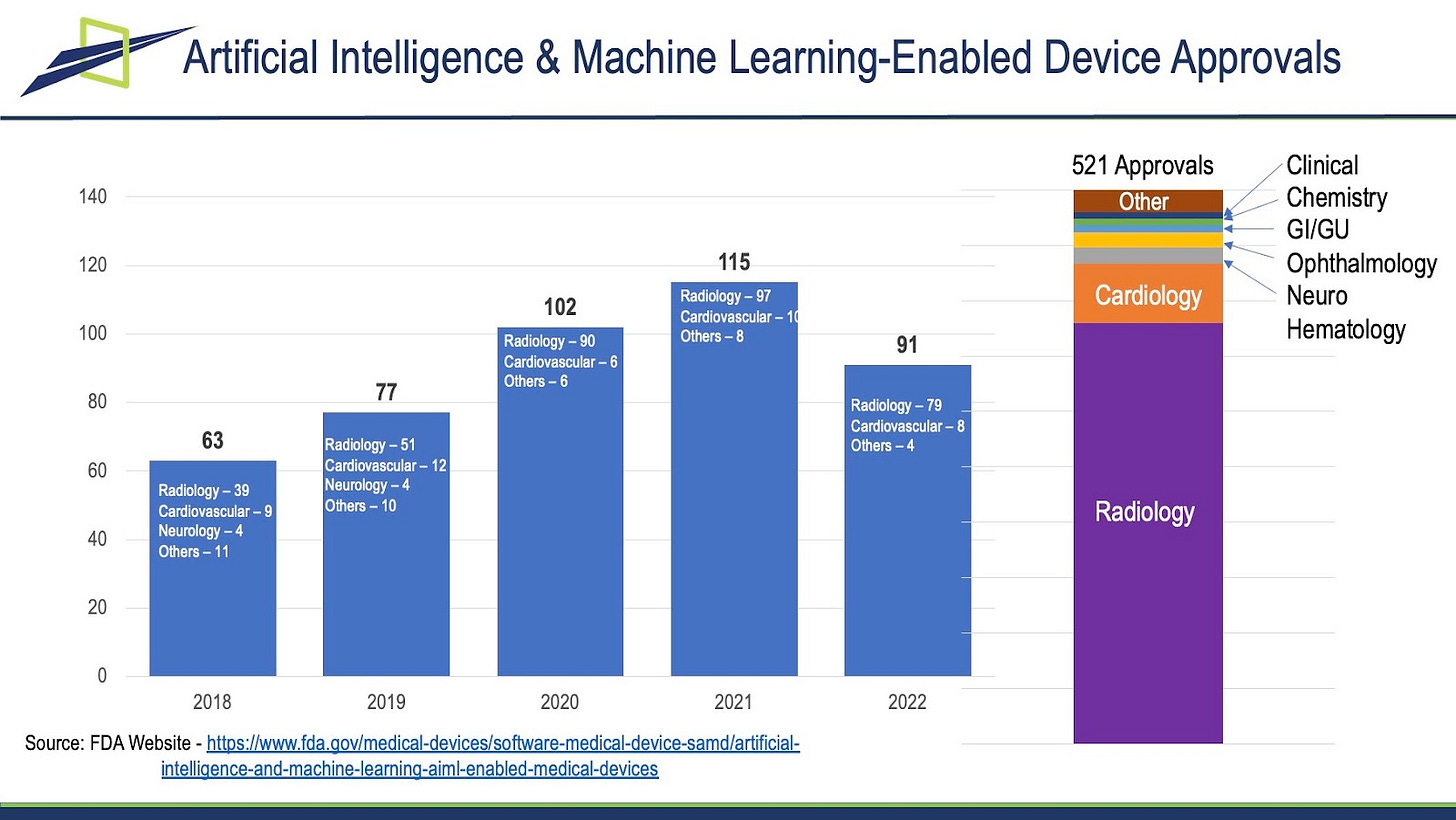

The clearest impact of AI in medicine to date is the well-established use of AI in diagnostic algorithms. The FDA has now cleared more than 500 algorithms using AI, the vast majority of which (80%+) are related to processing or interpreting radiological images (from MRI / CT / PET Scan / X Ray). If you want to get into the weeds, go to the American College of Radiology’s Data Central, which lists and sorts all of these approvals (242) by technology, by body part analyzed, by company, and more.

A new recent clearance is in the field of prenatal ultrasound. As in most of the existing algorithms, AI does not replace the reader but instead facilitates their read. The system “automatically selects views and anatomical structures, along with verifying quality criteria, during exams.”

Commentary: Probably obvious, but we expect many, many more of these algorithms. Most will be manufacturer-agnostic and work to improve the quality and / or speed of image interpretation. Moving forward, there are three important questions that need to be considered:

Will reimbursement change when AI is used - for the radiologist and for the treating physician?

How much human oversight will be integrated into the read process to make sure the AI driven result is correct?

Will clinical patients’ data generated be added to the learning dataset to improve the AI system - how will privacy and data ownership be affected?

The alert system that first warned us about SARS-CoV-2 is broke.

The very first warning the world received about the coronavirus that would cause the COVID-19 pandemic came from ProMED-mail, a disease-surveillance system run by the International Society for Infectious Diseases (ISID). ProMED (The Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases) has been around for nearly 30 years, was one of the first such systems to accept tips from non-government sources (including anonymous ones), and now bills itself as “the largest publicly available system conducting global reporting of infectious disease outbreaks.” And it’s falling apart, because it can’t get adequate funding.

The problem came to light this week when ISID shifted ProMED-mail to a paid-subscription model without the knowledge of the worldwide team of (barely paid) moderators who keep the system running. In a story following up on that announcement, STAT News reported that according to tax filings, ISID lost over $1 million in 2021. Science noted that ISID needs about $1 million per year to run ProMED, but a donation campaign in October 2022 raised only $20K. The subscription model, it turns out, is a last-ditch effort to try to save an organization that hasn’t paid its people in months.

Commentary: Think about that. We are just coming out of a global pandemic, and the alert system that sounded the first alarm about it is dying for lack of money. What does that say about our priorities as a global civilization? Surely someone somewhere with deep pockets can scrape together a million US per year to keep this thing running.

Can a bacterial profile in blood diagnose cancer types? Maybe…

The claims: A 2020 Nature paper found unique bacteria populations (the microbiome) in 18,116 tissue and blood samples collected for The Cancer Genome Atlas that proved highly accurate identifying cancer and cancer type. The same team published (Cell 2022) that this was also true for fungi (the mycobiome), although to a lesser degree.

Logically, these unique signatures make sense. Everyone has a wide range of bacterial cell types in their bodies, all of which compete with each other for local dominance. Cancer alters these microenvironments in ways that are unique to the tissue and cancer type involved, driving changes in the types and abundance of different bacteria: some will like the cancerous environment, others will not. Local weakness of the immune system within and around the tumor turbo-charges these alterations, enabling rapid microbiome adjustments.

However, the proof is in the data - and a recently posted bioRxiv preprint called the source data behind the Nature paper into question, as well as the analysis.

The first big issue the preprint authors raise: The paper compared DNA found in TCGA samples to a bacterial reference genome database (GenBank) that has been widely reported to be contaminated with stretches of human DNA. If so, bacteria can be reported to be present based on the human not the unique bacterial DNA, generating orders of magnitude too high bacterial reports, even including bacteria not found in humans at all (e.g. plant bacteria). See the chart for the preprint authors’ reanalysis in one cancer type.

And the follow-on issue: The original paper used a machine-learning system to analyze the (flawed) data. That data was “normalized” for AI training in a way that reclassified below-threshold results as above threshold, resulting in a garbage-in/garbage-out problem.

The Nature authors have since published a detailed rebuttal in a GitHub post. They reanalyzed a subset of their data to avoid the stated objections and still found unique signatures.

Commentary: Most importantly, this is how science is supposed to work - breakthrough work suggests a strong relationship, then peers pile in to evaluate and, if necessary, make changes. The problem comes when the initial headlines get reported before this dialogue reaches confirmation and consensus. In this case the system is working correctly - we know that reproducibility is a big issue in published papers, and only full and open data sharing can avoid it.

However, reproducibility is not the only question here - the other issue is explainability on the part of the AI systems being used to analyze the data. Relevant training datasets for these systems have become huge, discouraging human review - but such review is necessary in order to ferret out the inevitable grandfather errors (both systemic and random) that compromise the data and bias the learning process. The problem is then compounded by the black box of AI/ML algorithms. We have to invest in comprehending these systems at their beginning, when they are small, once giant systems get into clinical care it will be too late.

Food for Thought

Late-stage cancer diagnoses up due to pandemic delays

One of the ongoing debates in public health and clinical care is the use and value of population-based screening. The arena in which it is most accepted is that of cancer, but even there, acceptance is not universal. The debate centers around three issues:

Is the cost of broad-based screening worth the relatively small number of positive cases found?

Is the screening technology up to the task? Is it sensitive and specific enough to be useful without causing undue stress both on the system and on the individual being screened?

Does screening really capture cancers early enough to treat?

A new study published in Lancet Oncology answered at least one of those questions by looking at cancer diagnosis in the US between the beginning of 2019 through the end of 2020. The study is based on a national registry which includes more than 70% of all US cancer diagnoses.

What it found: Over this time period, early stage cancer diagnosis was down 20%, while the percentage of diagnosed cancers that were found in late-stage went up 7% overall. In Hispanic, Asian, and Pacific Islander populations, it went up by 10-11%. How did this happen? During the early months of the pandemic, more than half of cancer screenings were canceled - that’s about 35,000 planned screenings that never happened. So, does screening really help capture cancers early? You bet it does.

Quick Hits

There’s a new variant in town: EG.5 (aka Eris, yet another Omicron offshoot) is now the most common COVID variant in the US, at 17.3% of sequenced cases. With cases rising across the country, it might be time to start masking up in public again. Sigh.