Optical biopsy: a new standard for skin cancer?

Volume 12, Issue 13 | September 4, 2025

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The ultimate non-invasive Alzheimer’s test?

Testing before chemo: The importance of diagnostics

Are extracellular vesicles the key to successful MCEDs?

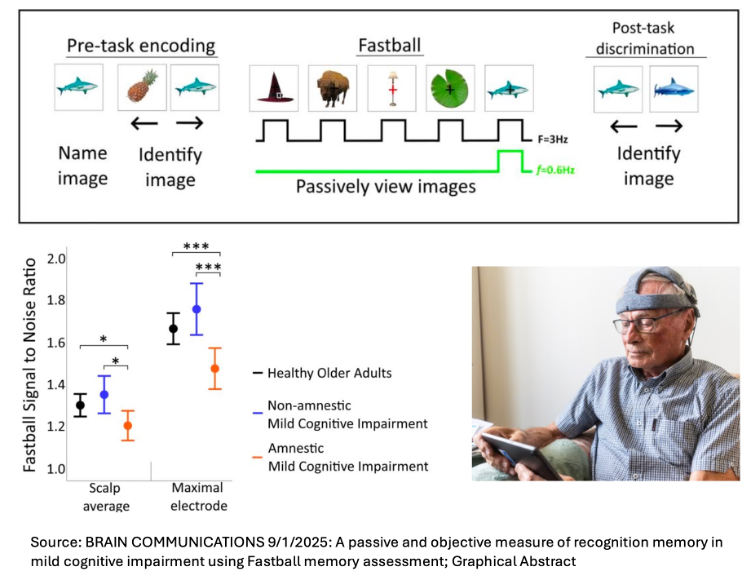

The ultimate non-invasive Alzheimer’s test?

Put some electrodes on your head and look at some images on a tablet for three minutes. How’s that for a non-invasive diagnostic?

The test is called Fastball, and it evaluates people with mild cognitive impairment for Alzheimer’s disease. Those electrodes measure brain activity in the hippocampus (where Alzheimer’s strikes first) while the patient looks at a set of images that they’ve seen before. Healthy older adults typically have difficulty recalling specifics but maintain their sense of familiarity (“it’s on the tip of my tongue…”), while those suffering cognitive impairment lose both.

COMMENTARY: The development of diagnostics and effective therapies are mutually reinforcing. Once therapies exist, we need inexpensive diagnostics to identify the patients they can help, while effective diagnostics guide research and improve commercial prospects for therapies. Alzheimer’s is right in the middle of this now, because for the first time there are two anti-amyloid drugs with a (very faint) glimmer of hope of effectiveness, and a less-invasive blood test for p-tau217 to find the people they might help.

A simple three-minute test like this has huge potential, especially as it may be able to catch cases of disease in their early stages, when they could be treatable. However, there are limitations to this work: a small group of subjects (54 controls and 33 with memory loss) and insufficient data to evaluate the inevitable positive and negative predictive value problems inherent to screening tests.

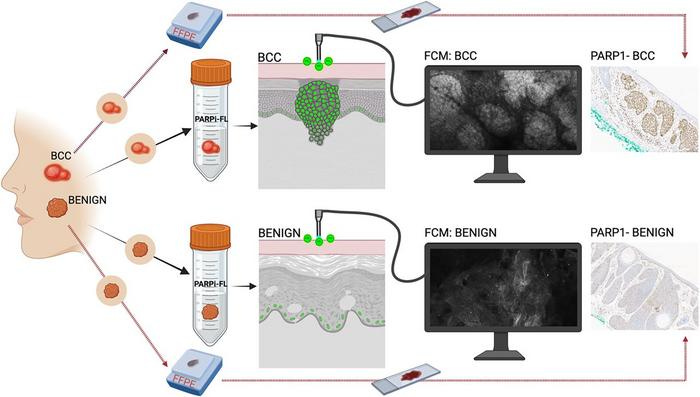

Diagnosing skin cancer with optical biopsy

Skin cancer is the most common type of cancer there is, and basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common type of skin cancer. Diagnosis requires a biopsy - for now. A new technique - something we’re calling an optical biopsy - may change that.

In an optical biopsy, clinicians apply a fluorescent contrast agent called PARPi-FL to the questionable area of skin and leave it there for two to five minutes. The contrast agent penetrates the skin, where cancerous cells take it up but normal cells don’t. Clinicians can then examine the skin with a fluorescent confocal microscope. If BCC is present, they can see it - all without breaking the skin. The technique has passed its early tests, but still needs to go through clinical trials in humans before it hits the clinic.

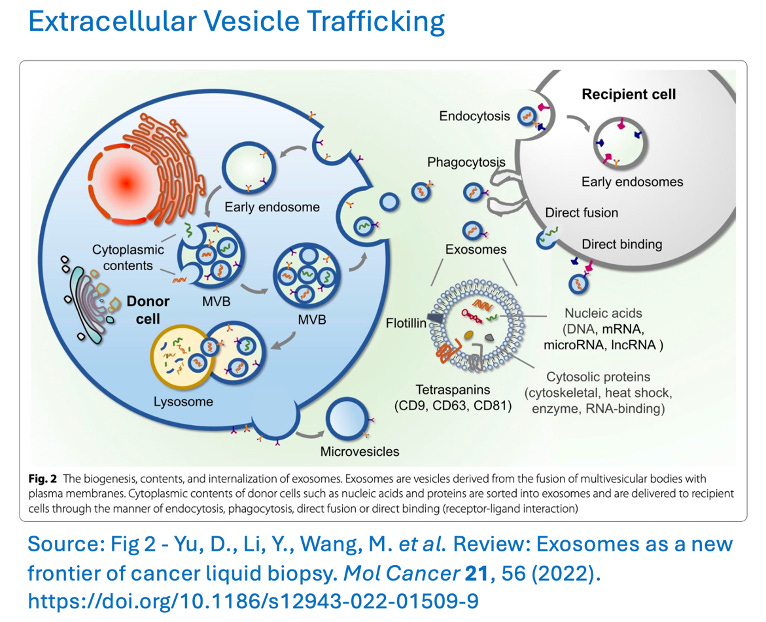

Are extracellular vesicles the key to successful MCEDs?

Despite their name, today’s multi-cancer early detection tests (MCEDs) struggle to identify early-stage cancers. (We and others have highlighted this problem in the past.) Their low sensitivity means that most positive results on these tests are actually false. A recent review by STAT News explores the possibility that circulating extracellular vesicles (EVs) might help resolve this central issue.

EVs are small packets of biologically active proteins and RNA that are trafficked from one cell to another. Whereas most free-floating DNA that’s circulating in blood comes from dying cells, EVs are created by both active and dying cells, making their contents a more timely snapshot of what is happening in cancer cells.

Additionally, EVs’ packaging protects their contents from breaking down. As a result, they contain diagnostically relevant cargoes such as RNA and proteins that are degraded too quickly in free circulation to ever be easily detected in a traditional liquid biopsy.

COMMENTARY: There are ongoing large clinical trials to see whether existing MCEDs, even with their current low sensitivity for early-stage cancers, will reduce cancer mortality in the long run. The challenge is that the long run takes a long time to figure out.

On the EV front, encouraging progress is being made, particularly for the hardest-to-detect early cancers, such as pancreatic. But even if EVs are the answer, we are a long way from knowing how much better those tests are - and an even longer way from seeing them in the clinic.

Testing before chemo: A reminder of the importance of diagnostics

Along with surgery and radiation, chemotherapy is a mainstay of cancer treatment. The way it works is simple in concept - kill the cancer cells with poison. But chemotherapy’s ongoing challenge has been figuring out how to kill only cancer cells, without harming the healthy parts of the body.

The problem extends beyond the need to ensure that the drugs don’t directly kill healthy cells. People undergoing chemo also need to be able to process and excrete the drugs being used to treat them. For folks with genetic variations that make it hard for them to do that, this can be a potentially deadly issue. And it only appears once they’re undergoing treatment - unless they get tested first.

A recent KFF Health News article covered this topic. It focused on 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and capecitabine, some of the most commonly used chemo drugs, which are broken down in the body by the enzyme dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD). In 2020, the European Union’s equivalent of the FDA began recommending that patients be tested before treatment with 5-FU and capecitabine to make sure they can make DPD. No such requirement exists in the US yet, but, as KFF Health News reported, “On Jan. 24, the FDA issued a warning . . . in which it urged health-care providers to ‘inform patients prior to treatment’ about the risks” posed by the two drugs. And on March 31, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network “recommended that doctors consider testing before dosing patients with 5-FU or capecitabine.”

COMMENTARY: This feels like a no-brainer to us. If you know a drug could be deadly, why wouldn’t you require testing to make sure it won’t kill patients? The hem-and-haw response we’ve seen is twofold:

Some test results are equivocal, so clinicians won’t know what to do with that, and

Some cancers move quickly, so these patients need to get chemo asap if they’re to have a chance.

To these, we reply that Europe seems to have a solution to these problems: If test results show anything other than obvious safety, start the drug at half the standard dosage - or if possible, switch drugs.

Bird Flu: Raw food infects cat

A cat in California contracted H5N1 flu and was euthanized after eating contaminated raw food, the FDA reported this week. The food in question was RAWR Raw Cat Food Chicken Eats sliders, which is sold nationwide and online.

COMMENTARY: (Liz puts on veterinarian hat.) Seriously, people, if you needed another reason not to feed your pets raw food, this is a good one. Cats are exquisitely sensitive to avian flu, and it is not a microbe that food companies routinely test for. Please, for your cat’s sake, pick a reputable canned food that makes you and your feline happy and feed them that. Thank you, and I’ll get off my soapbox now. (Removes hat)

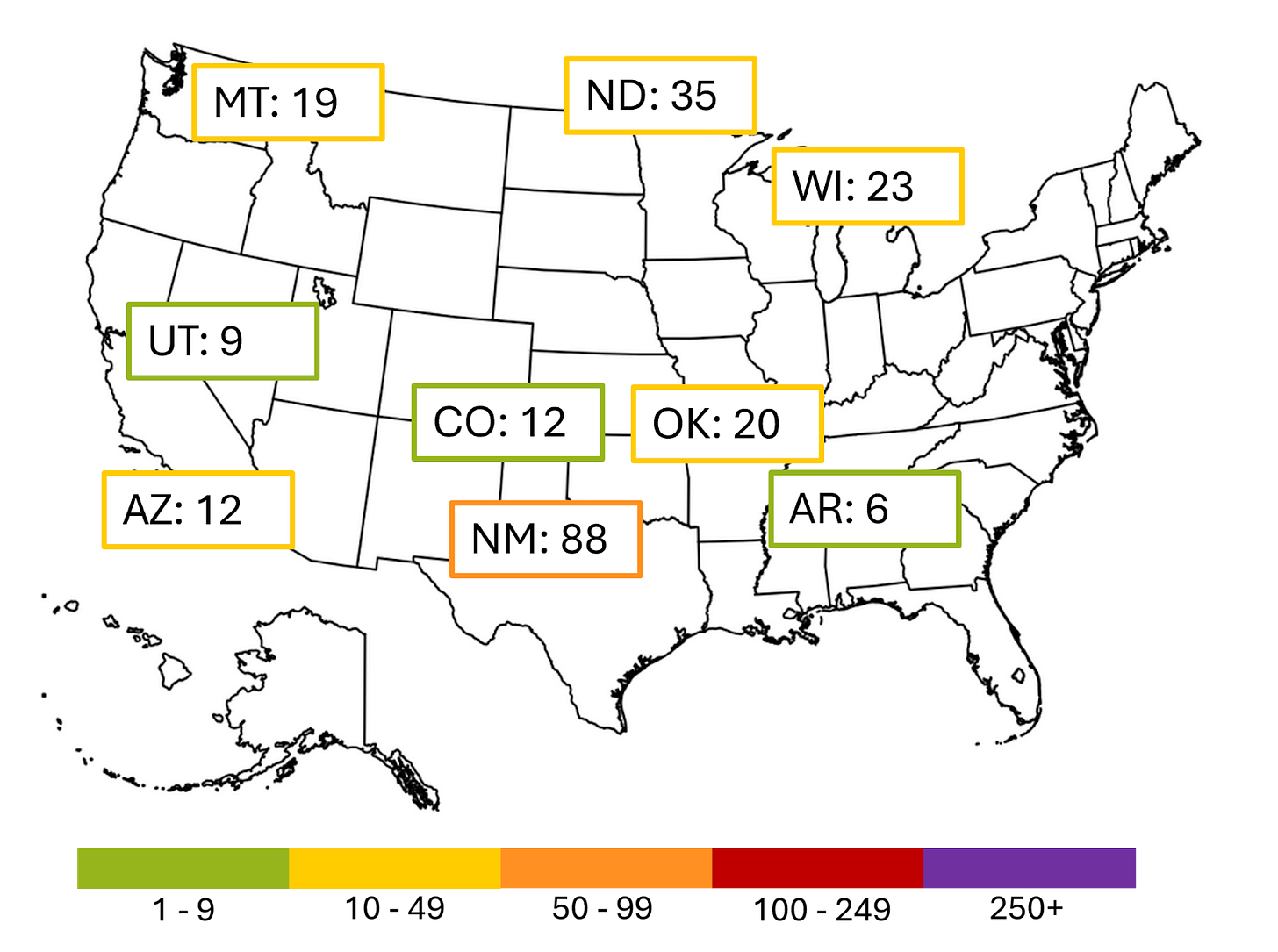

Measles

The current larger outbreaks in the US are shown below. The cases in New Mexico and Oklahoma are linked to the large outbreak in West Texas. Those in Arkansas, Arizona, Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, Utah, and Wisconsin are unrelated.

Thanks for sharing the insight about the EVs as a more real time snapshot. If you all or other readers know of any good reviews on how to isolate / capture them I’d be super interested to read it!