ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

A measurement that predicts Alzheimer’s cognitive decline

GAO report urges HHS to improve federal Dx testing

Lupus - the diagnostic odyssey at its worst

A curious little study that supports early MCED testing - kinda

A simple measurement predicts cognitive decline from Alzheimer’s

A measurement provided by two cheap and routine blood tests can predict cognitive decline due to Alzheimer’s disease, according to research presented at the recent European Academy of Neurology (EAN) Congress. The metric is the triglyceride-glucose index (TyG), which is often used as a marker for insulin resistance in diabetic patients. But for folks with Alzheimer’s, it turns out this number matters even if you don’t have diabetes. The scientists showed that non-diabetic Alzheimer’s patients whose TyG was high progressed to full-blown disease four times faster than those with lower levels.

COMMENTARY: A characteristic marker of Alzheimer’s is the breakdown of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The BBB protects the brain from many damaging influences from the rest of the body, including systemic inflammation. Since the brain metabolizes a large amount of glucose, it is not surprising that insulin resistance might have a similarly large effect on brain function. This work makes a strong case that metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance cause the BBB breakdown (along with other factors, including APOE(ε4) genetics- see this paper for more detail).

Of course, it is possible that metabolic syndrome as measured by TyG is just a biomarker for Alzheimer’s progression, not a driver. However, GLP-1 drugs designed to control metabolic syndrome have a beneficial effect on Alzheimer’s symptoms, which argues that the syndrome is a driver, not a passenger (Eric Topol seems to think so, and that’s our working hypothesis, too).

GAO report urges HHS to improve federal Dx testing

The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) has issued a report that “makes four recommendations and details nearly 100 ways the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) could improve federal diagnostic testing during a public health crisis such as a pandemic,” CIDRAP reported earlier this month. The four recommendations are directed at the agency’s secretary, asking him to:

Develop a collaborative, coordinated national testing strategy with clear roles and responsibilities for the parties involved

Periodically update that strategy with any lessons learned

Set up a national diagnostic testing forum for infectious diseases with pandemic potential that includes broad representation across federal and state government, industry, academia, and nonprofits

Make sure that that forum meets regularly, even when there aren’t diseases with pandemic potential around or on the horizon

Examples of actions the report says that HHS should take are shown in the graphic below.

COMMENTARY: We agree! These recommendations are 100% consistent with what we and many, many, many others said (shouted!) coming out of the COVID pandemic. They are also an important subset of the recommendations from the Testing Playbook for Biological Emergencies by the Brown University Pandemic Center and Assn of Public Health Labs (APHL) and described in Health Affairs in 2023. Note: Mara was one of the authors of said playbook.

Measles: Updates move to monthly

The outbreak centered in western Texas continues to slow and no major outbreaks in the US seem to be flaring up (knocks on wood). Starting in July we’ll be publishing updates on measles on a monthly basis unless something changes.

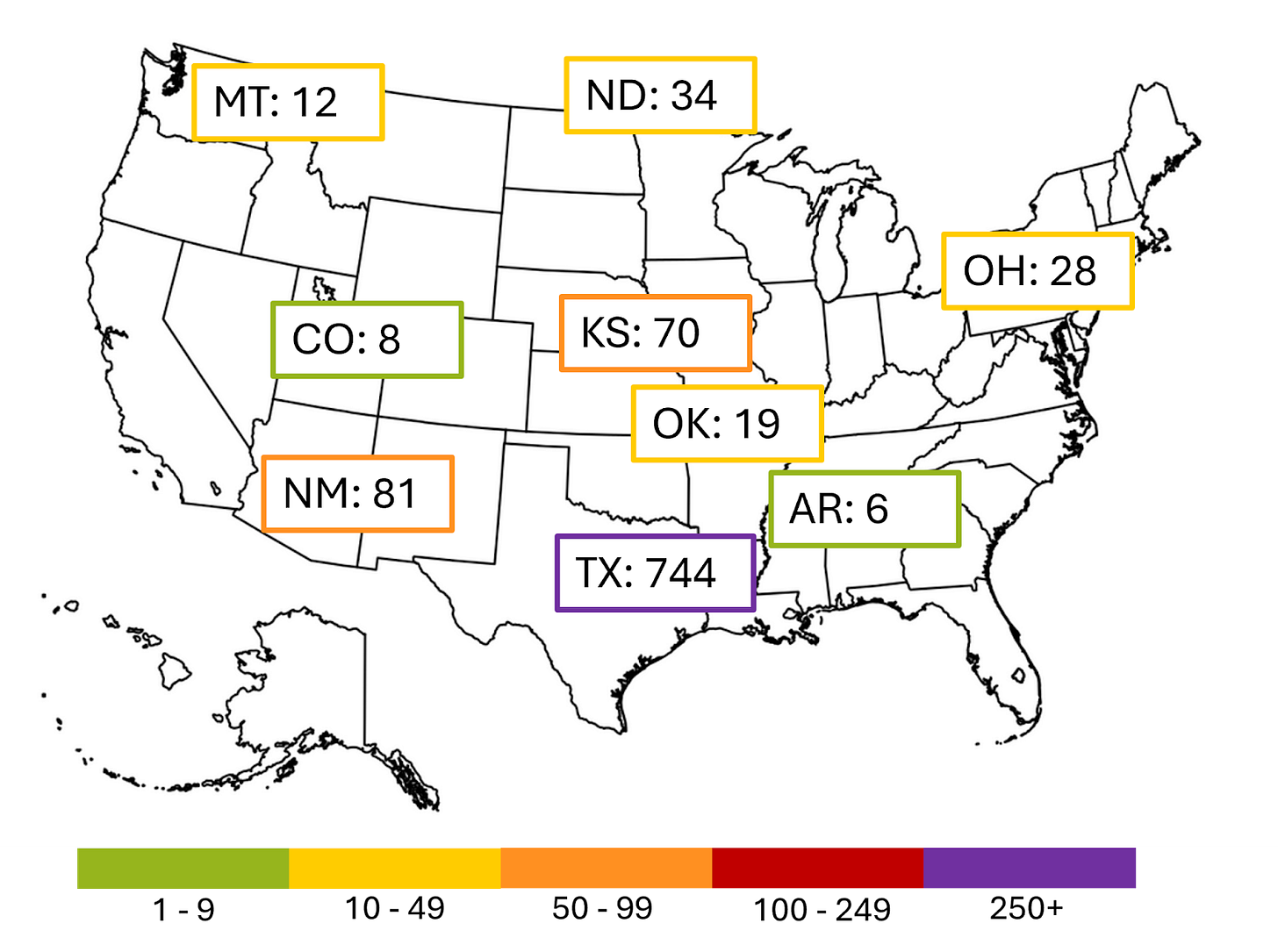

The current larger outbreaks are shown below. The cases in Texas, New Mexico, Kansas, and Oklahoma all came from the same source; those in Arkansas, Colorado, Montana, North Dakota and Ohio are unrelated.

Next-gen sequencing for the next generation

AAP recommends full sequencing for some kids to end Dx odysseys

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has updated its guidelines to recommend either whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing for children with intellectual disability or global developmental delays “in cases where a patient's medical history, family history, clinical examination, and corollary testing fail to deliver a suspected diagnosis,” 360Dx reported. The change from AAP’s 2014 guidelines broadens the scope of the genetic testing the group endorses - its previous guidelines recommended “more narrowly focused tests such as chromosomal microarray analysis,” 360Dx said.

England’s NHS to sequence every newborn

Late last week, England’s National Health Service (NHS) announced that it will conduct DNA sequencing for every newborn over the next 10 years. The decision wasn’t a big surprise, as it came after the start of NHS's pilot study that aims to screen 100,000 babies for 200 treatable genetic diseases. And these are not England’s first bold genomic initiatives. In 2020, Genomics England announced an ambitious plan to analyze five million genomes, including a half million through NHS’s Genomic Medicine Service and another half million through the UK Biobank.

COMMENTARY: Obviously, broad genetic screening like this can have unintended consequences - both positive or negative. Early this month the New York Times published an interesting article on the topic, The Ethical Minefield of Testing Healthy Infants.

What do folks think about personalized medicine? GoE aims to find out

The Genome of Europe (GoE) initiative has launched a survey in Estonia, France, Greece, Portugal, and Slovenia that aims to “assess citizens’ understanding and attitudes towards genetics and genomics-based personalized medicine.” GoE, which launched in November 2024, is a research project run by a variety of organizations across 27 European countries. Its ultimate goal is to create a “collective reference genome cohort (GoE Cohort) of European citizens, selected to mirror the genetic composition of the European population.”

COMMENTARY: This makes so much sense to us. As the technology behind personalized medicine continues to advance, we need to make sure that its end users - in theory, all of us - understand what it is and how to use it. This survey aims to find out whether folks across Europe are up to speed on the subject.

Lupus - the diagnostic odyssey at its worst

Many diseases are hard to diagnose, but systemic lupus erythematosus (aka lupus) is one of the toughest. Why? Let us count the reasons. We don’t have a confirmatory test for it. Too many of its symptoms overlap with other conditions. Many patients don’t have the classic symptoms. And finally, we’re very sorry to say, doctors often don’t believe that patients with lupus are sick. A UK-based study found that on average, it takes 7.5 years for someone with lupus to get diagnosed. In addition, the majority of patients in the study had to deal with “sustained diagnostic overshadowing.” In other words, clinicians thought the patients’ symptoms were either caused by either another disease or that the patients were making the symptoms up.

COMMENTARY: This study just emphasized how important it is that health-care professionals have knowledge of this frustrating disease. Early diagnosis is not only important for the patient’s state of mind and health, but for the cost of treatment.

A curious little study that supports early MCED testing - kinda

A small but fascinating study caught our eye recently. Johns Hopkins investigators dug into their sample archives and looked at plasma that had been collected as part of a heart disease cohort. Their goal: To see if early signs of cancer could have been detected by a plasma ctDNA test (similar to a multi-cancer early detection test / MCED).

They selected 26 samples from people known to have received a cancer diagnosis within six months of the plasma collection date, and compared them to 26 controls who had not received a cancer diagnosis up to 20 years later. Eight of the 26 cancer cases were detected, for a sensitivity of 31% - very similar to MCEDs now on the market. None of the controls were positive (i.e., no false positives). What was most striking: For six of the eight samples that tested positive, the archive also had a plasma sample from the same person that had been collected at least three years earlier - and four of those tested positive, too.

COMMENTARY: This is obviously too small a study on which to base firm conclusions. Plus, the cancer test used here looked for aneuploidy (the wrong number of chromosomes) and a subset of known cancer mutations, which is not exactly how most currently available MCEDs work. But if 60% of positive MCED results can be found 3.5 years before clinical diagnosis, it suggests that if you are going to do an MCED test in spite of their low sensitivity and high number of false positives, you might as well do it sooner rather than later.

Last month we told you about how ear wax can be used to diagnose cancer and diabetes. New research shows that it can also be used to diagnose Parkinson’s disease. That’s possible because the disease changes the makeup of compounds that ear wax releases into the air, and those changes can be detected using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry.

We will be on holiday next week for Independence Day. We hope the weather lets you get outside and do something summery, wherever you may be.