Also in This Issue

The single-drop pan-diagnostic is back (for real this time)

Early Cancer Detection tests - ready for prime time?

Adding liquid bx to standard tumor staging acronym

Bird flu update

New and Noteworthy

A full check-up from just a drop of blood? Quite possibly…

Did you think the idea of the one-drop pan-diagnostic was dead? Not one but two papers published this week indicate that it is not only alive but could be based on at least two different approaches.

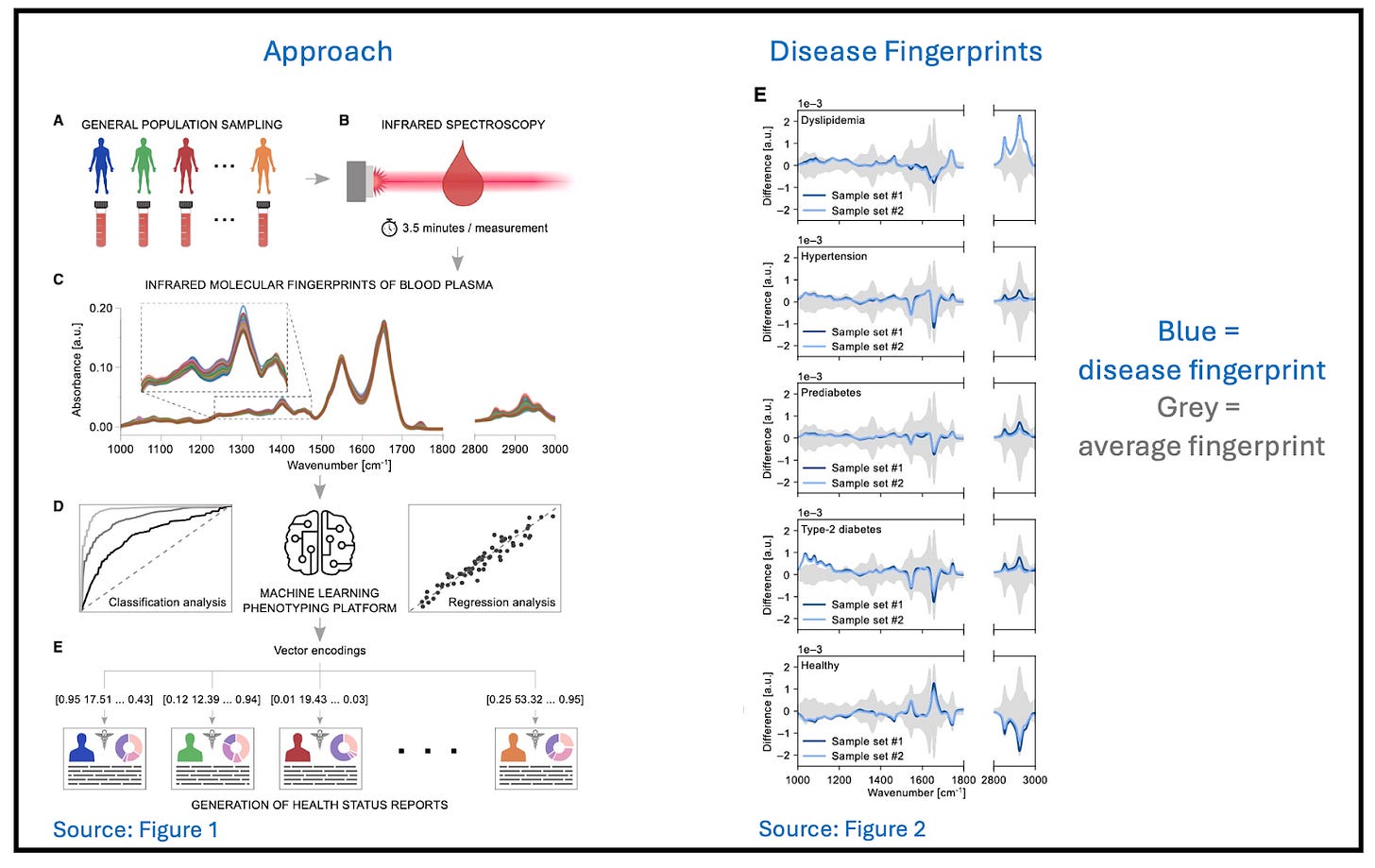

Using infrared spectroscopy

One set of researchers looked at the infrared spectrum of a drop of blood, using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FITR). Although it is impossible to identify blood components one by one using this technique, there is a stronger than (we, at least) expected association between unique spectral fingerprints and specific disorders, even among patients with many comorbidities.

The test was able to detect a range of metabolic disorders (both symptomatic and asymptomatic) as well as running 12 separate traditional tests all at the same time (triglycerides; total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol; hematocrit; erythrocytes; leukocytes; platelets; HbA1c; fasting glucose; albumin; and creatinine). In some cases, it did a better job of indicating disease than single-analyte screening tests did (e.g., lipids and glucose).

Commentary 1: it was impossible to read this paper without Theranos PTSD, but this approach is a totally different animal. Like many AI approaches, results are also explanation-free, and there is a lot more to investigate. But on balance, this is a very promising approach.

Using proteomics

The other set of researchers examined ~3,000 different proteins in ~41,000 individuals over 10 years to identify the smallest number of protein biomarkers needed to predict 218 diseases. Clinical history alone proved fully adequate for diagnosis of 15 of them, including many endocrine and cardiovascular disorders. But for 67 diseases, a fingerprint of 5-20 proteins improved on clinical diagnosis significantly. For celiac disease, using this “sparse” proteomic fingerprint had a likelihood ratio (the ratio of the probability that a test result is correct to the probability that it’s incorrect) that was 8x better than clinical diagnosis alone. For multiple myeloma and pulmonary fibrosis, the improvement was 7x; for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, 6x; and for ALS, 4x (see excerpt of Fig. 2 reproduced here).

Commentary 2: This paper is a useful indicator of where proteomics can have the highest impact on diagnosis. (It also points to novel therapeutic avenues.) We probably don’t need more than 20 proteins to diagnose disease, at least at current costs.

It also confirms that routine biomarkers need to be used more frequently in primary care and early specialty evaluation clinics. Differential diagnosis is difficult - in this study, it missed 75% of cases. Quantitative proteomics reduces this to 54%. That’s still not ideal, but it doubles the number of cases detected.

Bird flu update: Mandatory milk testing in CO, no asymptomatic disease in MI farmworkers

Dairy farms in Colorado must submit weekly samples from their bulk milk tanks for H5N1 testing until further notice, according to an order from the state veterinarian.

Two more poultry workers in Colorado tested positive for H5N1, bringing the national total of human cases to 11. No human-to-human transmission has been seen so far.

A Michigan study found no H5N1 antibodies in workers on farms where cattle were infected with the virus. This result suggests that asymptomatic bird flu is not present in people.

Commentary: Yay Colorado! Frustrating that the same thing isn’t happening in every affected state. As this post from Adam Kucharski’s Understanding the Unseen blog explains, we are at the point in this outbreak where “intervention is both feasible and has a lot of preventative impact for the level of effort exerted. And yet it’s not happening.” Astounding that after all we’ve been through, we’re still using hope as a strategy.

Food for Thought

Are MCED tests ready for prime time?

Are multi-cancer early detection (MCED) tests worthwhile? The promise of these tests is exciting, predominantly because of the E(arly): The hope is that these tests cause otherwise asymptomatic cancers to be detected early enough to intervene and extend healthy life. This week the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) published a Perspective (paywall) from WHO, laying out what we need to know before rolling out these expensive tests broadly (both NIH and the UK NHS have started large-scale trials to find out).

There are several intuitive and compelling arguments in favor (see “Dying to Find Out”), but this NEJM paper sets a high bar for adoption. We’ve listed their requirements below, in question form, with our answers.

1. Do pre-symptomatic signals of life-threatening cancers exist? Yes. Both tumor-specific and pan-cancer early signals are discoverable by next-generation sequencing of circulating tumor DNA.

2. Can an MCED detect those symptoms reliably? Sometimes. Current tests are least effective in early stages (I & II) but may be better at finding aggressive cancers.

3. Does early detection enable treatment that extends life? Data is mixed. Statistics show that patients diagnosed at early stages have longer overall survival than those at later stages, but how many aggressive cancers could have been found and successfully treated earlier remains an open question.

4. Is the harm from the inevitable false positives minimal? Probably not. For patients, there is anxiety, sometimes significant. For the health-care system, there is cost and follow-up time. Simply getting an appointment for the necessary follow-up test in a timely manner is a challenge.

Commentary: Even beyond the “E” in MCED, current less-invasive MCED tests will encourage more people to get screened, both earlier and more often, especially those with ambiguous symptoms. For many with true-positive results, this will almost certainly improve quality of life and survival, although death from versus with cancer complicates statistics (see this recent review).

From a public-health (and payor) perspective, there is resistance to even current screening practices. Adding expensive follow-up to an already expensive MCED test for the large number of people who will receive false-positives is going to be a big issue for individual payors - not to mention broader health-care systems, who aren’t ready for the potential influx of patients. Widespread MCED adoption is unlikely to meet its early expectations until clear answers arrive from the real-world trials that are just beginning.

Acronyms matter: adding liquid biopsy to tumor-staging standards

The biggest challenge for personalized medicine is getting busy clinicians to use it. For this to happen, the tests in question have to be not only clinically useful but familiar to the clinicians who must request them.

A recent paper addresses the latter issue by suggesting that a B for liquid Biopsy be added to the commonly used TNM staging system for cancer (Tumor size; spread to lymph Nodes; Metastasis). When a cancerous mass is removed, the patient’s disease level would be staged using a system called TNMB.

Commentary: This might sound like a very small step for mankind, but it is a necessary and big step for busy clinicians. It is only one of many improvements needed to bring modern but less-familiar diagnostic technology into the workup of all cancer patients.

Quick Hits

Athletes aren’t the only ones who had to make the cut for the summer Olympics starting this week in Paris - microbes did, too. A study published July 11th announced the six pathogens that researchers deemed highest priority to monitor in wastewater surveillance during the games. Poliovirus, influenza A, influenza B, mpox, SARS-CoV-2, and measles were chosen based on three criteria: analytical feasibility, relevance with regards to the event and to pathogen characteristics, and their value for informing public health policies. The slate of microbes was under review with the French health authorities at the time the paper was written, so we don’t yet know who made the final pathogen team.