Feature Focus on Misdiagnosis: A Description and our Prescription

Volume 8, Issue 10 | August 16, 2023

Misdiagnosis: How much, how come, and how to make things better

It’s been 23 years since the National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Medicine published their landmark report on misdiagnosis, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System. At the time, the report estimated that misdiagnosis caused 100,000 deaths per year in hospitals alone; it pointed to systemic issues as the primary root cause.

The diagnostic context since then has changed dramatically. Because more and better therapies are available in many cases (but not all), the stakes are higher: A missed diagnosis could now be a missed chance at survival, whereas before it might simply have been a misreading on which disease would kill you. Fortunately, physicians also now have a much improved arsenal of diagnostic tools that should - in theory - help decrease the chance that such a misreading happens.

How many people are harmed, and what disease states are involved?

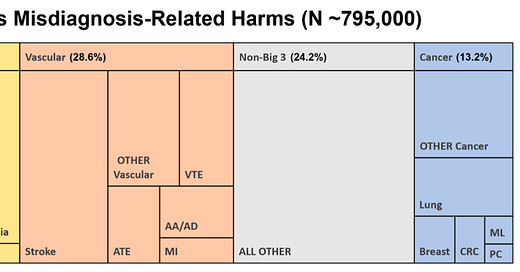

A recent paper in BMJ Quality and Safety provides a broad update to To Err is Human. “Burden of serious harms from diagnostic error in the USA” estimates that 795,000 patients suffer “serious misdiagnosis-related harms (permanent morbidity, mortality)” each year (range 598,000 to 1 million).

Overall, the good news - if there is any good news here - is that “only” 11% of cases involving the “big three” disease states (infections, vascular disease, and cancer) were found to be misdiagnosed; 4.4% of these cases resulted in serious harm. But 4.4% of the “big three” is a lot of people.

Looking more broadly, roughly half of the misdiagnoses involved only 15 diseases. However, it isn’t just highly complex conditions (e.g., sepsis at 10%) or rarer diseases (e.g., spinal abscess at 62%) that are misdiagnosed. It’s common stuff: 36% of aortic aneurysms; 18% of strokes; 23% of lung cancers. There are some exceptions: the intense focus on heart attacks for the last 25 years seems to have succeeded, as heart attacks generated a low 1.5% misdiagnosis rate.

Follow the money along with the impact

Misdiagnosis and diagnostic errors are also expensive. In a study of more than 350,000 paid claims in the US from 1986 to 2010, diagnostic errors accounted for 28.6% of paid claims and 35.2% of monetary payouts - just over 100,000 cases. According to this study in BMJ: Quality and Safety, “Among malpractice claims, diagnostic errors appear to be the most common, most costly, and most dangerous of medical mistakes.”

Who or what is responsible?

So why are these misdiagnoses happening? At the simplest level, the responsibility can lie in one of two places (or both): with the clinician or with the test. There are also critical infrastructural / systemic elements to consider, like whether the clinician’s choice of tests is hampered by cost or availability, or whether the test-ordering software makes it easier to find some tests than others. While we recognize that - as was the case back in the year 2000 - these elements may cause more problems than anything else, they are beyond the scope of this analysis. So those aside, the basic potential causes of misdiagnosis are the following:

Incomplete differential diagnosis (clinician)

Full portfolio of relevant tests not known or not considered (clinician)

Diagnostic tests inappropriate, given the differential diagnosis (clinician)

Test chosen were not the best ones in their class (clinician and/or test)

Test results inaccurate and / or not definitive (test)

Test results improperly interpreted (clinician and/or test report)

Pilot error - and how to avoid it in the future

So how well do physicians perform? Not very well, according to a study in PNAS last week, in which seven online case-vignettes were presented to 2,941 primary-care physicians. On average, 21% of cases were misdiagnosed, but some physicians performed much worse than others. The top quartile of performers were wrong just 5.4% of the time, but the lowest quartile were wrong in 45% of cases. Teaming improved fourth-quartile performance by a third, but still left these physicians misdiagnosing patients nearly one third of the time.

Commentary: There are all sorts of possible issues with these studies, particularly the fact that none of them examines the root causes of misdiagnosis in a quantitative way. Without understanding which causes carry the most weight, we can’t focus our efforts on the solutions that will move the needle the most.

If teaming with another physician helps clinicians who need assistance, perhaps “extreme teaming” - with colleagues or AI or both - will help even more. The PNAS study shows that there’s certainly room for improvement in that area, and technology is barreling ahead in that direction. We’ll need other studies in a few years to find out.

One strategy on which we have found disappointingly little focus involves increasing the quantity and quality of clinicians’ education about diagnostic tests. We would like to see:

Required diagnostic-related coursework in medical and nursing school, as well as in educational programs for other health care professions

Add a diagnostic focus (maybe a checklist) for all Year 3 and Year 4 rotations of medical school

Board exams for medical specialties that include questions about relevant diagnostics

Required continuing education about diagnostics for physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other health care providers.

We have three more recommendations that go even further. (We recognize that these are unlikely at best, but we want to be bold here.)

Review CMS / Medicare’s “Never Events” in the context of misdiagnosis and consider what needs to be added going forward, particularly regarding AI.

Add diagnostic review committees to all accountable care organizations and large practices to better ensure peer-to-peer quality review.

Establish transparent industry standards for test quality, including sensitivity, specificity, and indeterminate results.

Misdiagnosis is disastrous, especially for patients with serious rapid-onset diseases. When that happens, the best-case scenario is “just” a delay in getting the right treatment. (The worst case is . . . the worst case.) Rapid diagnostics and imaging tools are increasingly available to close this gap, but physicians have to know what they need to test for, when to test, what’s available to test for that, and which test is the best among those options. Then they have to interpret the results correctly. That’s a lot to ask of human beings. The tests just have to give correct results - and that’s plenty hard enough.