Calculating your personal cardiovascular risk

Volume 12, Issue 24 | November 20, 2025

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Is this test the Lyme disease holy grail?

A faster way to find fungal disease

Continuous BP monitoring via smart ring - is it worth it?

A new way to calculate CVD risk, based on new BP guidelines

If you’ve had kids, you’re familiar with the charts that pediatricians use to monitor children’s growth. They let you know how the height and weight of your offspring compares to that of children of the same age and sex assignment at birth, giving you a general sense of whether yours are on the taller or shorter or heavier or lighter ends of the spectrum.

An interactive, grownup version of these charts is now available online - but instead of growth, it measures heart health. You enter your vital info into the American Heart Association’s PREVENT™ Online Calculator, and it tells you your risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) over the next 10 and 30 years as compared to other folks your age and sex. (Make sure you have your most recent medical records handy. You’ll need to type in data like your HDL cholesterol levels and systolic blood pressure, among other things.)

The calculator and the equations that underlie it are the centerpiece of a new set of blood-pressure guidelines that the AHA dropped in August. They replace the Pooled Cohort Equation (PCE), which underestimated 10-year CVD risk for some racial and ethnic groups.

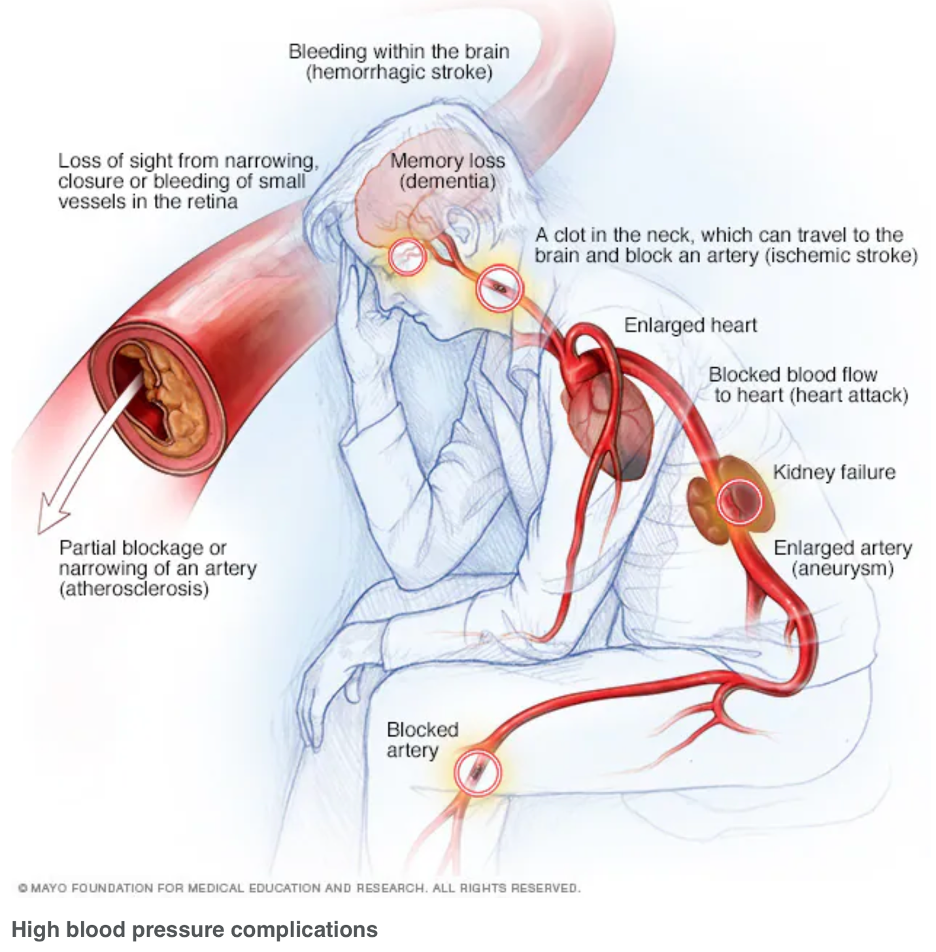

The updated guidelines also emphasize at-home monitoring (hence the online calculator) and recommend starting medication at a lower blood-pressure level than before (130/80 mmHg if your 10-year risk of CVD is at or above 7.5%; for pregnant people, it’s 140 mmHg systolic, 90 mmHg diastolic). The push for earlier treatment in general results from mounting evidence that high blood pressure is linked to dementia and other forms of cognitive decline. For pregnant folks, it reflects growing evidence that tighter blood pressure control may help to reduce the risk of serious complications.

Is this test the Lyme disease holy grail?

Researchers have developed a Lyme disease test that can diagnose the disease earlier than traditional tests and can help distinguish between an active and past infection. The new diagnostic is actually a suite of three different droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) tests to detect different types of Borrelia bacteria, the microbe that causes Lyme disease.

Results indicate that they can “detect as few as five to 10 bacterial cells,” CIDRAP reported, and had 91% sensitivity. The work was done with archived samples, and the study’s authors expect sensitivity will improve when fresh or even frozen samples are used. The research was presented last week at the Association for Molecular Pathology 2025 Annual Meeting & Expo.

COMMENTARY: This is a small study, but man, if the work holds up, it’ll be exciting. Right now, active Lyme disease is incredibly frustrating to diagnose. Only 25% of infections present with the bulls-eye rash that people associate with Lyme, and antibody tests often show up negative during the early stages. Then, when people test positive later on with those same diagnostics, there’s no way to know whether they have active disease. The antibodies the test detected could just be evidence of infection sometime in the past.

This test could be what all of us who live in Lyme disease country have been waiting for - a test that definitively tells you whether the bacteria are in you right now. That would allow clinicians and patients to feel more confident about prescribing treatment, and would allow them to do so earlier, when it’s more likely to be effective.

A faster way to find fungal disease

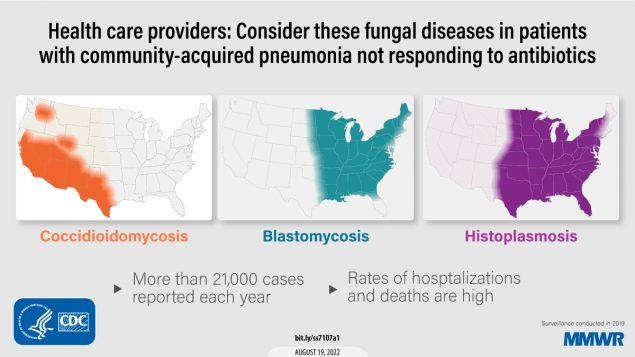

Though Lyme gets the most press, there are other regional microbial diseases to worry about, too. (Oh joy - more diseases to be worried about!) Three particularly problematic ones are fungal diseases:

Histoplasmosis, which centers around the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys

Blastomycosis, present throughout the eastern US but most common in those same river valleys, plus around the Great Lakes and in the Southeast

Coccidiomycosis (aka Valley Fever), which lives in the Southwest

All three are caused by exposure to contaminated soil, and they all present with respiratory +/- other symptoms that can look like a lot of other things. And traditionally they’ve all been a pain to diagnose, requiring either lengthy fungal culture or relying on antigen and/or antibody tests with spotty accuracy.

Enter a multiplex PCR test that targets three genetic regions, each unique to one fungus: ITS1 for Histoplasma, BAD1 for Blastomyces, and A2/PRA gene for Coccidioides. According to results presented at last week’s Association for Molecular Pathology 2025 Annual Meeting & Expo, the test is 100% sensitive and specific, doesn’t require DNA extraction (thus reducing turnaround time), and runs on standard clinical lab equipment.

Continuous BP monitoring via smart ring - is it worth it?

The maker of one smart ring “has formally petitioned the FDA for clearance to continuously monitor blood pressure,” MedPage Today reported earlier this month. This past week the FDA approved the GONDOR-AS trial to validate the tool.

COMMENTARY: Is this technologically possible? Yes. Is it worthwhile? Maybe.

Over the past decade, both sensors and the electronics to interpret their signals have become small and cheap enough to embed in earbuds, rings, wristwatches, and skin patches, offering a cornucopia of continuous monitoring applications.

The underlying technology is almost magic: green LED skin-reflectivity dynamics (aka photoplethysmography - PPG for short) and “AI-inside” algorithms infer BP from age-adjusted pulse wave velocity (PWV) single-point measurements. PWV is an even better predictor of cardiovascular health than BP alone, because it directly measures arterial stiffness. That’s what causes the short, sharp pressure pulses that damage small blood vessels, driving calcification/embolism, vascular dementia, eye retinopathy, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease, among many other problems.

There is no question that BP monitoring is essential. While cardiovascular-related mortality has declined by nearly 70% over the past 50 years, it remains the number-one cause of death, both in the US and around the world. The more challenging question is whether continuous monitoring is more clinically useful than routine single-point measurements. It may be, but the bigger problem is that most people with high BP are not being monitored at all. And few of those will afford these sophisticated devices (see the MedPage Today article for more concerns).

Other applications of continuous monitoring have come under question (see our recent discussion of fetal heart rate monitoring). Yes, there are many situations in which continuous monitoring is clinically essential, for example when rare events with severe consequences are a possibility (e.g., sepsis, pacemaker management) and in cases where trends can provide early warning to drive interventions (e.g., glucose levels in Type I diabetes). However, the biggest commercial opportunity for continuous monitoring is the “wellness” business, where benefits are much more speculative. See this excellent review of continuous glucose management by the Diagnostic Detective and our prior discussion of CGM for more.

We’ve talked before about using breath as a diagnostic sample - using petri dishes carried by drones, researchers have now collected breath samples from critically endangered North Atlantic right whales. They found distinct microbial patterns in the samples - some patterns showed up in thin whales, others in healthy-looking ones, for example. The drone-based, noninvasive technique allows researchers to monitor the animals’ health noninvasively, and allows them to access animals that would otherwise be difficult or dangerous to reach.

Fantastic article. I agree with continuous BP monitoring. While I use an ambulatory BP cuff for patients whose BP is all over the place, I don't see the need for continuous monitoring. In fact, I think it will lead to more data overload and potential harm. But well have to wait and see how the research unfolds, maybe I'm wrong.