Also in This Issue

Are MCED test trials worth it?

Liquid biopsy evolves - now with EVs

Bird flu update

New and Noteworthy

Liquid biopsy started with ctDNA. Now we’re inspecting EVs, too

We’re getting close to the 15-year mark with liquid biopsies, and progress has been impressive. So where did we start, and how far have we come?

When liquid biopsies began, they were primarily focused on finding circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) with mutated genes. We say that like it’s easy, but it’s one heck of a challenge. Circulating DNA is shed mostly from dying cells and has a half-life of only 90-120 minutes. While blood contains “lots” of DNA (“lots” being 5-10 billionths of a gram per ml of blood plasma, equivalent to 1,500-3,000 genomes), most is from healthy cells. Only one in 1,000 of these DNA fragments comes from a dying tumor cell. In other words, a test has to find all 1-3 mutated copies per sample to avoid a false negative.

That this feat can be accomplished at all is an amazing technical achievement of enormous diagnostic value, but it was just the beginning. In addition to detecting mutated ctDNA, current tests can now spot patterns of methylation or fragmentation in ctDNA that indicate the presence of cancer and/or reveal how aggressive a tumor is.

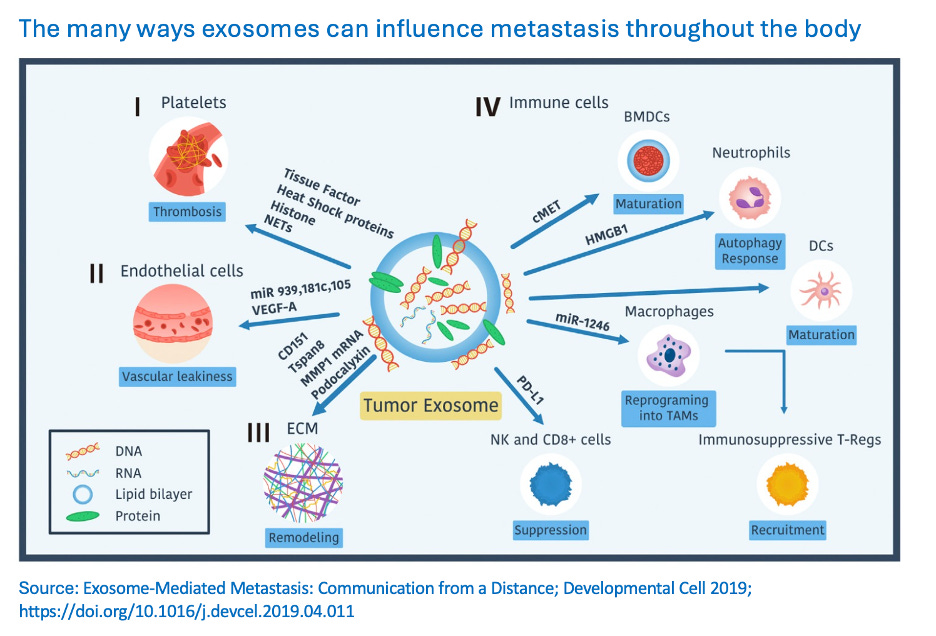

Now there’s a whole new target for liquid biopsy. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are (very small) parcels that use the circulatory “freeway” system to communicate with other cells throughout the body and transport cargo to and fro. This April, a paper in ACS Nano showed how molecules on the outside of the EV act as a “fingerprint” (a “shipping label” showing where the EV is headed and what it transports). A study published in Nature Medicine in June showed that blood-borne EVs that originate in the brain can reveal brain disorders (frontotemporal dementia and ALS in this paper, but Alzheimer’s disease may also end up being detectable). And a paper that appeared in EVs’ own journal last week (yes, there’s a Journal of Extracellular Vesicles) describes how important microRNAs (non-protein-coding RNAs that regulate cell dynamics) in EV cargo are to disease detection.

Commentary: Since the first effective liquid biopsy in 2010, the pace of development has been exponential (see this 2023 Nature Editorial for a brief summary). EVs have a lot of untapped diagnostic potential, and may prove even more revealing than mutation detection alone. The EV “shipping label” may help identify where metastasis can take root, while the microRNA cargo may reveal malignancy potential. Beyond cancer, if EVs turn out to be a (or the?) primary cell-to-cell cargo trafficking process, studying their dynamics may aid a broad range of disease diagnostics.

One test to rule them all?

While age in years is one of the most reliable predictors of disease and mortality, it is very unreliable at making predictions about health status and quality of life for specific individuals. Over the past few years there have been several attempts (e.g., this 2019 paper) to understand which proteins drive the health limitations that we associate with aging. The answer would help us understand if changing our behavior really can alter the way we age, and it could identify key proteins that may be targets for future treatments.

In a study published last week in Nature Medicine, researchers used AI to analyze levels of 2,897 proteins in 45,441 UK Biobank individuals. They were able to identify “204 proteins that accurately predict chronological age,” 20 of which (ProtAgeGap20) had the most effect.

In addition, levels of the 204 key proteins were used to create a “ProtAgeGap204” score: the difference between biological age and chronological age - biological age was based on the levels of those proteins. The top 5% of folks had a protein signature that was 10 years “younger” than the bottom 5%, and the incidence of “diseases of aging” varied even more between the two groups (see this extract of Figs. 2 and 4).

Commentary: This study shows correlation, not causation, so the ProtAgeGap20 tend to be proteins that are involved in the consequences of morbidity rather than the causes. Nevertheless, this is yet another example of the untapped potential that a simple blood draw could have on patients’ willingness to be more thoughtful about how their lifestyles affect their health.

Bird flu update: Farms still aren’t testing

Only 30 of the approximately 24,000 dairy farms in the US are participating in the USDA’s voluntary H5N1 testing program, the New York Times reported.

The CDC is partnering with Trupanion, a pet health-insurance company, to develop a disease-surveillance system. They plan to start by keeping track of health-insurance claims that could be related to H5N1.

Food for Thought

Are extensive, expensive trials of MCED tests worth it?

The hopes for multi-cancer early detection (MCED) tests rest upon four foundations (paraphrased by us a few weeks ago):

Early signals of life-threatening cancers exist

A blood test can reliably detect them

Early detection reduces death from cancer

Harms of false positives and negatives are minimal/acceptable

Several clinical trials of individual MCED tests have been carried out with generally supportive results (e.g., Galleri and Cancerguard), and overall assessments of the field are available (chart here reproduced from this comprehensive review). However, skepticism persists.

The BMJ Investigations Unit recently published its concerns about the utility of these tests - and about an extensive trial that the UK’s National Health Service is conducting to evaluate one of them (Galleri). (The US NIH is running a similar trial - the results of both won’t be available for some years.) The critique cites concerns that the UK NHS program is not structured to assess any of the four foundations adequately. As of now, per peer-reviewed, vendor-funded research, sensitivity for stage I-III localized tumors is only 43.9%. For Stage I alone it’s a low 16.8%. These results question foundations #1 and #2, while implying a failure on #4. Even the NHS itself stated that the trial’s interim results were “not compelling enough” (yet), but the agency didn’t publish the data behind that assessment.

Net net: The BMJ believes that dedicating a $200 million NHS trial to just one vendor is a mistake (one observer is quoted as saying that “it is a clear-cut case of public risk and private profit”).

Commentary: We are enthusiastic about the potential of less-invasive diagnostics in general and blood tests in particular. The extent of what can be discovered from this source would have been unbelievable 10 years ago – progress has been astonishing.

However, there are real risks involved with jumping too soon on limited evidence. The E (early) in MCED is unproven, and without it, there are better tissue-of-origin-focused tests available to address symptomatic patients. We acknowledge the convenience of a blood draw vs. a more invasive test. But, if early results of these trials are underwhelming, using these tests will become hard to justify, and a whole field of diagnostics may be set back years, perhaps decades.